It has now been sixteen full years since that scorching July 11, 1995, when units of the Army of the Republika Srpska, personally led by General Ratko Mladić, entered the captured – or, as they used to say at the time, and as many still say to this day, the “liberated” – Srebrenica.

What followed is, I would say, well known to everyone, even though the scale and very essence of this event have been denied, relativized, or downplayed in every possible way and countless times.

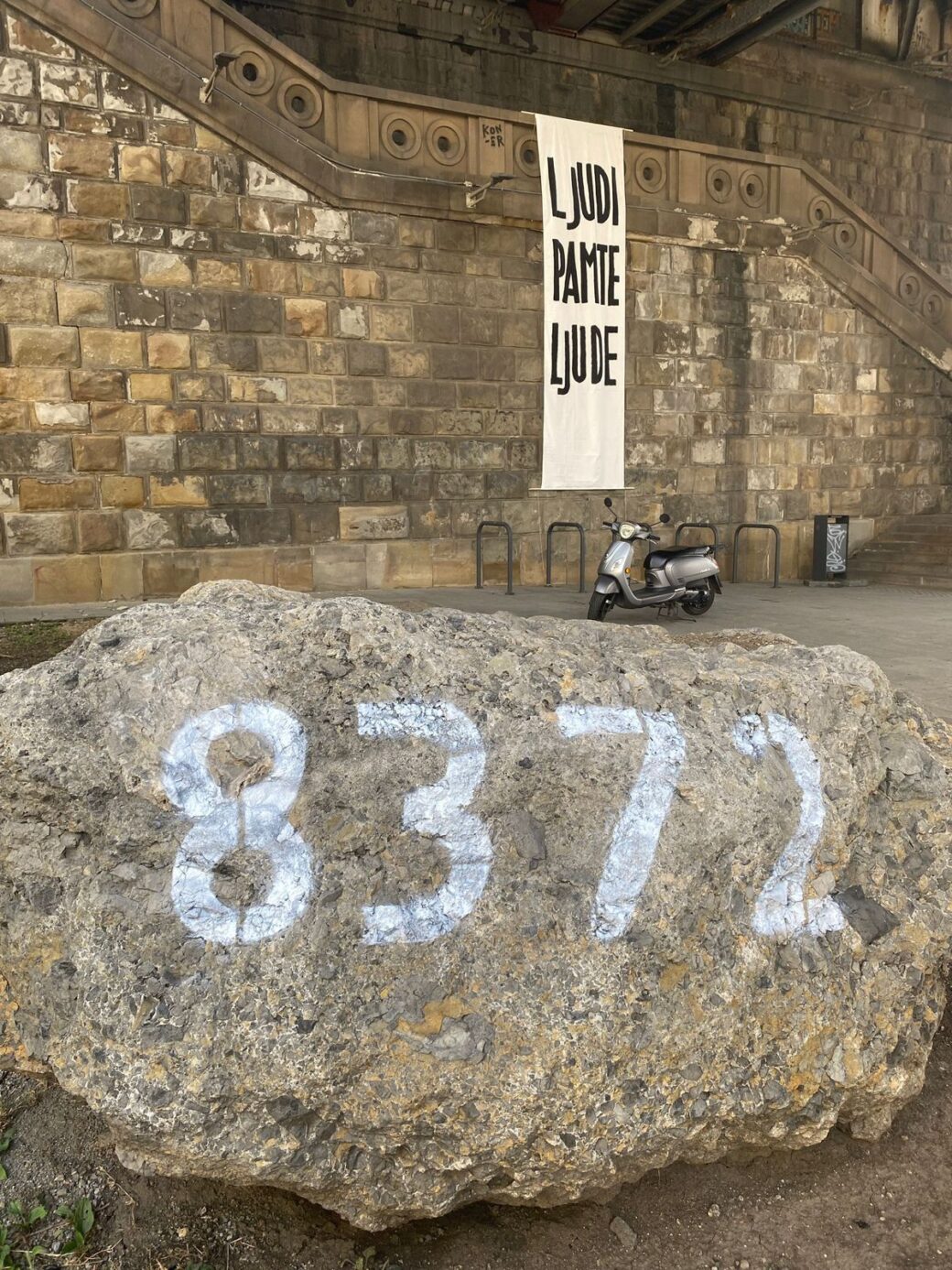

Still, one thing is indisputable, no matter how hard many try to convince us otherwise or at least skillfully pull the wool over our eyes. At several locations in the vicinity of Srebrenica, following the occupation of this Podrinje town, Serbian forces carried out the largest massacre in Europe since the Second World War, killing in an organized operation more than eight thousand males aged between 12 and 77.

Setting aside that cruel judgment of the age span of the so-called “males,” executing such a number of people in such a short time, and at the same time displacing tens of thousands of women and small children, requires even more cruelty, but also effort, as well as infrastructural and strategic capabilities.

That what took place in Srebrenica in the summer of 1995 was ethnic cleansing in its most horrifying imaginable form is beyond any doubt. The triumphant, arrogant, and haughty behavior of Mladić and his military commanders upon entering the occupied town, as well as the cowardly behavior of the Dutch UNPROFOR troops, serve as textbook examples of how, under certain circumstances, that intoxicating combination of extreme brutality of the conquerors and miserable indecisiveness of the designated defenders – whose own well-fed asses’ safety is the most important thing to them – results in ethnic cleansing to the fullest extent.

Or, to stop beating around the bush – in genocide.

I don’t think it needs to be especially argued that the task of carrying out genocide is not for the faint of heart. But it is worth noting that the one in Srebrenica was executed with astonishing precision and considerable discretion—exactly the way it is done by someone who knows very well what they are doing.

To this day, we do not know exactly what the final moments of most of the victims looked like—we can, at best, only imagine—but we have, however, had the chance to see a home video made by members of the Šid-based paramilitary group Scorpions, in which the brutal execution of six young Srebrenica Bosniaks (the youngest of whom was only sixteen years old) is shown, carried out near Trnovo, which is a full 180 kilometers away from that town. This gave us a glimpse into the unjust, almost unimaginable humiliation and pain in which the victims—often far too young, still beardless boys—were killed, with so little right to an honorable death. Like dogs, truly. But also into the enjoyment and ease with which the executioners carried out their gruesome task. And the fact that the videotape was, for a time, available under the counter in certain video rental shops in their hometown of Šid casts a particular light on the whole matter and points to a specific snuff quality of that horrific footage. For it was clearly suited to the (erotic?) taste or at least the morbid curiosity of other potential viewers—not just the perpetrators of the crime themselves. Which eventually brought the perpetrators before the face of (however limited) justice, so it turns out, some good did come of it after all.

However, for the revisionists and skeptics among us—and let’s not kid ourselves, there are many—nothing has ever served as sufficient proof of anything they, for certain emotional reasons, were not prepared to believe in. Including the genocide in Srebrenica. And there’s no help for that. At every attempt at reasoning, they immediately launch into arguments composed of paranoid delusions, blatant lies, and all sorts of nonsense, or they automatically shift into their favorite, perverse game with numbers and drag it out endlessly—as in, it wasn’t eight thousand victims but a mere three thousand, and the whole world knows that three thousand people killed in one place over a few days can hardly be called even a light massacre, let alone—please!—genocide?! And when they see that even that doesn’t work, they eventually slip into that oh-so-Serbian “And what did they do to us?” mode, and tilt endlessly like a broken pinball machine. In such moments, the only thing a person can truly do is withdraw.

And yet, what happened during those hot and terrible July days of 1995 in Potočari, Kravica, Sandići, on the banks of the Jadar, in Tišća, Grbavci, Pilica, Kozluk, and yes, even in distant Trnovo, is not going anywhere. It is impossible to forget something like that or leave it behind. Srebrenica isn’t going anywhere. It has nowhere to go. It will be with us forever and will keep returning to remind us just how deep all those dreadful abysses of our collective potential run, and how capable we are of being worthy, successful, the very best—precisely when we are at our very worst.

*

What took place in and around Srebrenica during those July days sixteen full years ago represents a horrifying demonstration of the ultimate consequences of that infamous statement by Milošević with which the Yugoslav wars, after all, began: “If we don’t know how to work, we know how to fight.”

Upon triumphantly entering the hastily abandoned and devastated town, Ratko Mladić, general and sociopath, and therefore, naturally, a Serbian hero, a so-called СРБ-in, gave a statement in which he declared Srebrenica a “gift to the Serbian people” and emphasized, with his characteristic clarity of thought, that the time had come to “take revenge on the Turks in this area after the uprising against the dahije”, “dahije” being a specific class of tyrannical Ottoman officers or leaders in a long gone past.

After what??

On whom?!?

Some time later, however, it became clear what this thoroughly psychotic madman had been so rapturously rambling about. It took only a few days for his ultimate “revenge on the Turks” to be fully carried out. In the broken and exhausted, half-alive Srebrenica civilians—or at least the “males” aged 12 to 77—he never for a moment managed to see ordinary people, children and old men caught and trapped in the most horrific madness of war, but only and solely those terrible “Turks” from his own childhood nightmares, of which he had clearly never managed to rid himself. That’s what happens when, from an early age, you are fed badly cooked national myths for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

When I watch the former General Mladić today—that fearsome man who once radiated military arrogance and a sense of boundless power, and who so visibly enjoyed the war—how he now sits broken, helplessly whining and wailing in the courtroom of the Hague Tribunal, begging to have his pathetic little cap… uh, hat… returned to him, moaning that they “won’t let him breathe,” and when after that I watch yet again, for the umpteenth time, all those distressing recordings from the days of his greatest bloody glory, paid for with thousands of lives—those videos of his entry into ghostly deserted Srebrenica—I cannot say that I’m not glad that the instigators and perpetrators of all the terrible crimes of the nineties, not just this one in Srebrenica, are, slowly but surely, one by one, getting what they deserve. And that there is, after all, some kind of justice, however elusive and strange. Because we’re talking about the all-too-lenient justice of Scheveningen, which makes room for prison cells better equipped than VIP rooms in rundown Serbian or Bosnian hospitals, and also for wireless internet, long visits, multi-day stays, cooking and language classes. I’m not sure Mladić’s victims enjoyed any such justice, but it is evident that the kind of justice my sadistic mind desires—the one summed up in the old phrase “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth”—will never come to their executioner.

And that makes it meaningless to expect it.

I’m not glad about that—but what can I do.

On the other hand, what I find even less bearable—or, if you will, what fills me with deep depression—is the fact that the Serbian people, so irreversibly afflicted by national and ethnic rigidity and arrogance, have not, in the entire span of sixteen years, managed to look upon the Srebrenica massacre with a different, purely human perspective. And that, in fact, shouldn’t be all that difficult. It would be enough to think of the victims as civilians, as ordinary people—me and you, our parents, life or marital partners, children, relatives, friends, just ordinary people who wanted from life only that little bit of happiness we all believe belongs to us by birthright, but who, it turns out, were searching for it in a catastrophically wrong place and were, well, what can I say, you know it already, cowardly slaughtered during those horrific six or seven or nine or however many July days in Srebrenica, sixteen years ago.

By the Serbian army, led by a pure Serb.

Ratko Mladić.

In the name of the Serbian people, to whom he gifted the whole of Srebrenica—and thus all its victims—as a present.

However, despite that, even today many among us refuse to accept even the most basic human responsibility and to show what I believe any person we consider normal and emotionally balanced, regardless of nationality or ethnicity, could only show in the face of such a catastrophe: compassion. Sixteen full years after the Srebrenica genocide, many still, like Mladić, see only some sort of “Turks” in the victims of Srebrenica—imaginary Serbian arch-enemies from a paradoxical cartoon version of national history that we are taught generation after generation.

Well, in a way, it’s clear why that is so. Politicians, the Church, the education system, the media—they all work hard to once and for all wean the Serbian people off any form of humanity, any form of empathy toward the other. Especially toward our closest neighbors. And on the other hand, understandable or not, all of that is still utterly devastating. And sad in a way that could hardly be sadder. That dull awareness that the same fatal delusions which gripped us during the 1980s and 1990s are still with us today. The heavy suspicion that they take on even more terrifying meaning when we realize that they are, to a significant degree, being embraced by the youngest generations as well. And that there is still, among us, a frightening number of those who would, tragically, fail even the most basic test of humanity.